Collision Course

The deer came crashing through the underbrush heading straight for me. I was rooted in place not by fear; I just didn’t know what else to do.

They were on me in a flash. A doe with her yearling and fawn crashed onto the trail running headlong toward where I stood. At the last instant the doe perceived my presence. After a startled double-take she swerved uphill, ready to plunge back into the forest. But just as suddenly she slid to a halt and spun in place. I was between the doe and her offspring.

The yearling, a moment behind its mother, halted less than 10 feet from me and took a few hesitant steps toward the safety of the trees. But the desire to reunite with its mother as well as natural curiosity kept it from darting off. The fawn, trailing the other two, came to a screeching halt on the trail 20 feet from where I stood. It looked puzzled.

We all took a few moments to catch our breath and assess the situation. My stillness bewildered the deer and we all waited for the other shoe to drop. From my side, I was wondering what spooked these animals and whether it was coming this way.

My equanimity seemed to diffuse the tension. And after a few minutes of mutual contemplation, the yearling darted past me to join its mother. The fawn negotiated a broader arc, giving a wide berth to the strange looking biped.

A Little Bird Told Me

As the deer melted into the forest I felt triumphant! This encounter was not the result of happenstance. I detected the deer more than a minute before they arrived and positioned myself to best observe them. Score one for bushcraft!

When I first started observing wildlife, I looked for any advantage to get closer to animals. I flirted briefly with wearing camouflage clothing. But I soon realized how useless it is. Camouflage doesn’t work when you’re the one moving. Much to my frustration the animals almost always perceive me before I even notice they’re around. This was because I was usually hiking while the animals were still. They heard me coming, they saw me moving, and they were gone before I could even think about reaching for my camera.

But what if I could see them first? What if I could receive advance notice that animals were coming? I could be the motionless one. I could locate them before they knew *I* was there.

Bird language lets you do this, and more.

Toucan Play This Game

Birds like this Steller’s Jay can become our allies and guides.

(Image by Alan D. Wilson, www.naturespicsonline.com, cc 3.0)

Birds see and hear everything that goes on in the forest. They must, their lives depend on it. The downside to their hypervigilance is that they give you away when you are out looking for wildlife.

Birds are the early warning system of the forest. Wildlife tunes-in to what the birds are saying. When birds spread an alarm, wildlife skulks away before you arrive. For a person walking at a normal pace, animals can get as much as two minutes warning. Animals don’t run from us, they stroll!

If you are attuned to what the birds are saying you can have the same advantage. You can detect unseen or distant wildlife. You can tell its direction of travel. You can see them before they can detect you.

Learning bird language also helps minimize your own disturbance. When you’re aware of what causes birds to alarm, you can alter your behavior when out in the field. You can cultivate a “routine of invisibility” that decreases your sphere of disturbance while increasing your sphere of awareness.

To someone unfamiliar with bird language, the results are astounding. You will appear to have supernatural powers. But bird language is not difficult to learn. Our hunter-gatherer ancestors were professionals. As a result, our brains are well adapted to the task by millions of years of evolution. Learning bird language does not convey supernatural powers. It gives you super-natural powers1!

Bird Language Basics

Red-winged Blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus) issuing a territorial call

Besides awareness, the secret to bird language is understanding birds’ “tone of voice.” Humans are naturally equipped to do this and beginners do surprisingly well. Bird language groups the “tones of voice” into 5 basic types of calls:

- Song – This is a normal “baseline” behavior. All is well in the forest.

- Companion calls – Bonded pairs like to keep in touch with one another as they forage. These calls can be part of the baseline. But they can also become an early warning of trouble.

- Territorial Aggression – It is important not to mistake these behaviors for alarms.

- Adolescent Begging – This baseline behavior can also be mistaken for alarms.

- Alarms – Understanding alarm calls is the key to knowing when something is not right in the forest.

Advanced bird language practitioners can even distinguish between ground predators and aerial ones by the type of alarm they hear.

Alarms also have “shapes”. The shape of an alarm refers to how the warnings propagate through time and space. They have delightful names like “plow”, “hook”, “sentinel”, “popcorn”, and “bullet.” The shape of an alarm allows you to infer the animal that caused the disturbance along with its location, direction and speed.

The Bird Sit

One way to learn bird language is to attend a “bird sit.” I was fortunate to attend one last week that also featured a lecture by author and bird language teacher, Jon Young.

The event was held at a working farm that operates as part of community supported agriculture. I enjoyed walking among the animals and in the nearby fields.

The Bird Sit was held at Tara Firma Farms. It’s mission is to create a sustainable source of food and allow the people who consume the food full access to the farm.

Female Downey woodpecker (Picoides pubescens). The farm is managed to provide good habitat for wildlife.

The day was overcast with an almost constant drizzle. But the damp and the cold did not dampen our spirits. About 30 students spread over a hillside overlooking a pond that reflected the moody sky.

The students found spots to sit or concealed themselves at various locations. The “sit” is divided into 3 10-minute periods. As the students find their spots, they create disturbance. So the first period is mainly to observe the disturbance and allow the environment to return to baseline. Human voices would disrupt the behaviors we came to observe. So an instructor imitates a crow’s CAW-CAW at the end of each 10-minute period.

The overcast and rain made it a challenge to remain motionless and keep warm.

The students at their sit-spots on a hill overlooking the pond.

The students noticed different aspects of what was going on around them. This created a rich picture at the debrief.

After the sit, we compared notes about what we observed. For example, the students created a large sparrow “bird plow” as they moved to their spots. A goose slipped into a bed of cattails where many other species sought shelter. Toward the end of our sit, alarm calls swept across the fields as a North American Kestrel shot overhead in a swift descending glide. Alarms also betrayed a family of deer “ghosting” in the mist through an oak covered hillside.

Most of the students witnessed only a small piece of the puzzle. But by pooling our observations we were able to assemble a story that matched each of the student’s observations. The complete picture provides the feedback the students needed to explain their experiences.

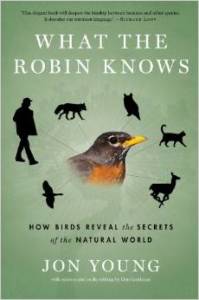

What the Robin Knows

The honored guest speaker was Jon Young. Jon wrote What the Robin Knows, which I consider the definitive book on bird language.

The honored guest speaker was Jon Young. Jon wrote What the Robin Knows, which I consider the definitive book on bird language.

Jon spoke about “nature connection.” He argued that our society has lost its traditional connection with the natural world. He outlined the potential consequences for individuals and for society as a whole.

Jon described the program he founded to teach nature connection using bird language. His organization has partnered with the Audubon Society to offer their programs at all Audubon centers throughout the country and parts of Canada. The program rolls-out this year and is intended primarily for children. But it will provide opportunities to learn bird language to anyone interested. If you would like to learn bird language, I suggest you contact your local Audubon Center to see when they will offer a program.

As someone interested in promoting nature awareness among children, I was impressed with Jon’s approach. I was also struck by his view that we need to develop a curriculum to teach nature connection. He concluded is talk with the thought, “Education has a process. Recreation has a process. Connection needs a process.”

Learn bird language. You won’t Egret it!

I strongly recommend these references for beginners interested in learning bird language.

More Birds on NatureOutside

Birds Think You are a Scary Dinosaur

What we can learn from a Harrier’s Butt

Where do Birds Go When it Rains?

For fun facts and useful tips, join the free Bushcraft Newsletter.

Your unspotted female Nuttalls looks suspiciously like a Downey woodpecker. Major tells are the lack of spots on the upper wings, shorter beak, and large white patch on the back of this bird, which Nuttalls do not have. Not to mention lack of spots on the belly.

DK, Thank you so much for taking the time to point out the error. I misidentified the Downey woodpecker as a Nuttall’s. I will correct the caption on the picture. Thank you!