What animal is the size of a Chevy Suburban, weighs as much as two American football teams (offense and defense), and dives 2,000 feet below the ocean’s surface?

Elephant seals (Mirounga angustirostris) are amazing creatures. And I’m lucky to live near a colony. These dwellers of the deep spend their entire lives at sea. But they come ashore to molt, give birth, and mate. Every year I try to visit them during the height of mating season.

Ano Nuevo

Ano Nuevo State Park is a picturesque beachfront and natural preserve that spans 6.5 square miles. The area received its current name from Father Antonio de la Ascension, chaplain for the Spanish maritime explorer Don Sebastian Vizcaíno. Vizcaino’s ship sailed by the area on January 3, 1603.

Looking across the coastal prairie. Ano Nuevo Island is in the distance.

Up to 10,000 elephant seals return to Ano Nuevo each year. But this wasn’t always the case. The first colonies of seals were not reported until the 1960’s. And there’s no historical record of elephant seal bones in the middens of the Quiroste people who inhabited the area. So the elephant seals are a recent phenomena. One theory holds that California’s grizzly bears were the only predators that could harm elephant seals ashore. So the seals did not begin colonizing the mainland until until humans extirpated grizzly bears from California.

But the human-elephant seal relationship wasn’t always rosy. At one time hundreds of thousands of elephant seals inhabited the waters off California. But people slaughtered them for their blubber in the 1800s. Elephant seal oil was second only to sperm whale oil in terms of quality. And it was easier to walk up to an elephant seal on the beach and shoot it than to harpoon a whale at sea.

By 1892, there were fewer than 100 individuals left alive along the Pacific Coast. Many people believed that elephant seals were already extinct. But a last colony remained on Guadalupe Island, Mexico. Fortunately, the Mexican government protected the colony in 1922. All the elephant seals in California are descendants of those survivors.

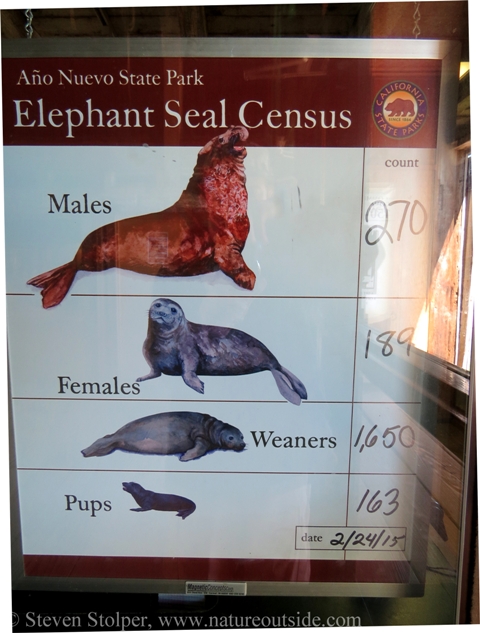

January is the best month to visit the colony. The beach is swarming with gigantic males battling for territory. Females are giving birth and nursing their young. But my visit this year occurred at the end of February. By this time most of the seals have returned to sea. The population is dominated by weaners.

Weaners are elephant seal babies that have finished nursing. But they are not fully developed. Their eyesight is poor, they do not know how to swim, and they do not know what to eat. So they hang out in groups on the beach and try not to get trampled by rampaging males. They continue to develop and begin to explore their surroundings. This makes trouble for the park rangers and docents. The weaners end up in unexpected places and the rangers have to reroute park visitors.

The remains of the lighthouse and fog signal station built on Ano Nuevo Island in 1872. The keeper’s house provides a home for Brandt’s and Pelagic Cormorants and California Sea Lions.

From November through March, docents escort visitors through the colony. With so many seals in such a small area, the escorts keep the visitors safe. Flattened tourists are bad for business!

Our group meets at the visitor center and begins a half-mile walk to the assembly point where we meet our guide. The weather is stunning. Sunlight glitters on the water and a warm breeze ripples across the grassland. Ano Nuevo is notorious for its cold and rain. So I find myself shedding layers as I labor under my daypack.

But weather is a double-edged sword. A beautiful day for humans is too hot for elephant seals. The seals languish in the balmy 68 degree heat. They prefer the bottom of the sea. So it’s best to visit during a cold snap when the seals are more active.

A Twisty Path

Our guide meets us at the entrance to the colony. His distinctive red jacket makes him easy to spot against the sand.

Approaching the colony

As we pass a warning sign, the guide explains, “They are fast for the first 20 feet.”

I don’t worry much about my safety. Elephant seals are simply too big to care about us puny humans. I’ve never been threatened by a seal in my many years visiting the colony. And if I ever do see a seal undulating toward me, I plan to model my behavior after the guide. When he runs, I’ll run too.

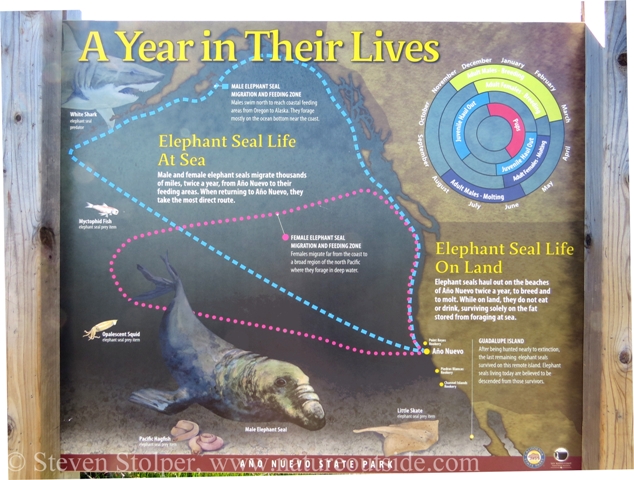

A second sign we pass explains the seals’ life cycle.

Notice that the males forage in different areas from the females. The males are so much larger that they must forage in colder waters to find the food they need.

We draw near the colony and hear the seals before we see them. Male elephant seals sound like a Harley Davidson motorcycle starting up in a small enclosed garage. The babies make high pitched screams.

Only 10% of males get a chance to mate. The dominant males occupy the prime beachfront property and force the less dominant ones inland. Rangers jokingly referred to the inland area as “Loser’s Beach.” But in the spirit of political correctness they changed the name to “Bachelor’s Beach.”

We skirt some of the bachelors as we approach the main colony.

A number of males block our way

You would be surprised how easy it is to stumble upon a 4,000 lbs animal unawares

We approach a hill where we hope to observe the seals. But plans change rapidly in an elephant seal colony. A group of weaners have moved into the area and blocked our way. The ranger reroutes our group to a different location.

Weaner detour

Skirting another sleeping male we negotiate our way onto the beach.

Let sleeping seals lie

A Face only a Mother Could Love

Northern elephant seals are the second largest seal in the world (the southern elephant seal is the largest). The males grow to 13 feet (4 m) in length and weigh up to 4,500 pounds (2,000 kg). The females are smaller at 10 feet (3 m) in length and 1,500 pounds (600 kg).

Since it was the end of February, most of the seals have gone. We do not see any of the big bruisers. As I gaze across the beach it is like arriving at the end of a party. Everybody who’s anybody has left and the stragglers are passed out on the couch.

Our viewpoint above the beach

Seals on the beach

Ano Nuevo provides an amazing backdrop to view these creatures

Don’t bother me, I’m sleeping…

Solitary at sea, the seals like to bunch up while on the beach (weaners).

Solitary in the water, they practically lay on top of each other on the beach. When viewing weaners, it’s important to note that the older animals are usually smaller. While nursing, a mother elephant seal transfers 40% of her body weight to her infant. But once she is gone they are not eating. In fact, a general rule is that if you see an elephant seal on land, it is not eating.

After a month nursing, the mothers depart the beach. But on the way off the beach they mate again. But the females are too weak to gestate. So the embryo delays development for about 3 months. Eleven months after departing the beach, the mothers return to give birth. Adult females are almost perpetually pregnant.

Death on the Beach

Also on the beach is the corpse of a California sea lion (Zalophus californianus). California is in the midst of a mysterious sea lion die-off. This is the third year in a row that starving young sea lions are washing up on California’s beaches. Almost 500 emaciated animals were brought to rehabilitation centers since the new year. This is much higher than usual and nobody knows what is happening. Scientists suspect that unusually warm ocean currents have disrupted fish migration. This would throw the sea lions’ food supply into chaos.

The corpse of a California sea lion

Running the Gauntlet

At the water’s edge, males lie in wait. Unable to mate when the large males were around, they hope to impregnate females as they return to the sea.

This male hopes to mate with a female as she tries to leave the beach

Lying in wait, this male reminds me of a crocodile

The females only want to mate with dominant males, so these males try to ambush the females as they leave the beach.

If the females can get past the ambushers, they must face yet another threat. Scientists counted 110 individual great white sharks within the triangle formed by the Farrallon Islands, Pt. Reyes and Ano Nuevo. They identified 80 individuals off the coast of Ano Nuevo when the seals are on the beach. Needless to say, I don’t sea kayak off the coast of Ano Nuevo!

Once at sea, the females can finally feed. Females dive as deep as 2,000 feet to find prey. Most of their predators (sharks) do not hunt below 300 feet. The guide explained that the seals can catnap as they dive. They are neutrally buoyant until 50 feet. Below 50 feet they sink. So the females “corkscrew” down while asleep and wake at the bottom to feed. This is marvelously efficient and they can remain underwater for up to 20 minutes.

Sleeping Beauty

We leave our vantage point to circle around the beach. As we do, we passed a 10 foot male sleeping with its nose in a pool of water. We tread carefully not to wake the beast.

Approaching carefully. We need to slip by this sleeping male.

My pictures don’t do a good job of conveying their enormous size.

The entire group slips by without disturbing ‘Sleeping Beauty.’

Looking at our previous position from our new overlook. In January, this beach would be teaming with seals.

Hidden Midden

As we climb to our new observation point, several in our group notice a strange feature in the sand.

A strange feature in the sand

Seashells litter the sand far from the shoreline. There are also pieces of rock. It’s a midden!

When the Quiroste people inhabited the region, they feasted on this spot. The long buried shells and stones are detritus from their activity. The Quiroste were rich in natural resources. They had access to olivella shells used for beads and currency. The Quiroste also had a supply of Monterey chert from a seldom exposed reef off Año Nuevo Point. Chert, like obsidian, is used to fashion stone tools. This wealth made the Quiroste an important tribe in the region.

A close-up of the midden. People are not permitted to walk on it. But the seals often do.

Looking uphill at the midden. It’s sheltered by hills with a nice view of the water.

Farewell to Seals

From our new vantage point, we look down upon a group of weaners. Both the people and the seals are getting tired so we end our walk through the colony.

Looking down on the weaners.

Solitary at sea, they enjoy company on the beach

I wonder what it’s thinking as it looks at us? (weaner)

Not too impressed…

References

Related Articles on NatureOutside

The Elephant Seals of Ano Nuevo

Mysteries on the Beach (Part 1)

If you like this article you might like to read others in the Trips Section and the Nature Section.

For fun facts and useful tips, join the free Bushcraft Newsletter.

Great story. Brought back memories of our Ano Nuevo hike to the seals, August 2013. It was a fantastic adventure and one that I still cherish. Would love to do it again.

Gene — It is truly wonderful to be so close to these enormous animals.