Mines, ghost towns, and furnaces: If that doesn’t make for an exciting hike, I don’t know what does!

I step out of my car eager to explore the area at the south end of northern California’s Santa Clara Valley. It’s a radiant morning and I ready myself for the long hike. Old mining equipment lines the trailhead. The rusting iron hulks speak of a past unrecognizable to those of us living in modern times.

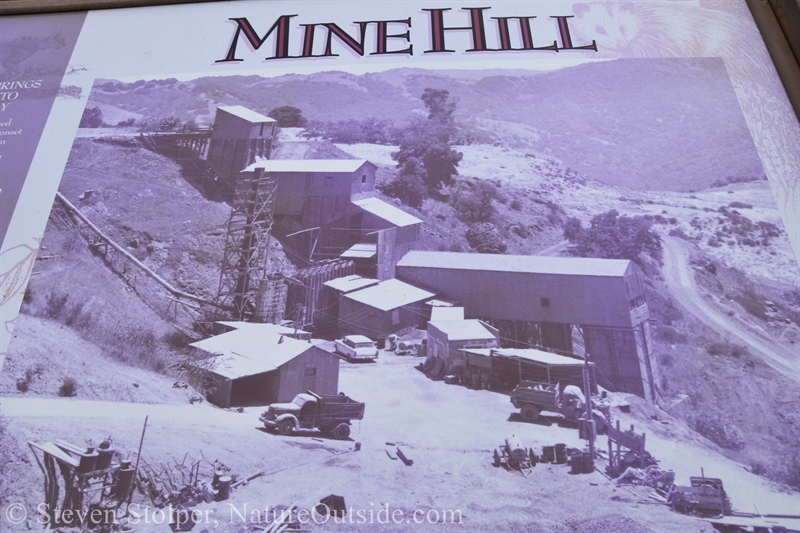

Before the Santa Clara Valley became “Silicon Valley” it could have been called “Mercury Valley.” It was one of the world’s premier sites for the mining and production of mercury. The mines are closed now and the land has become Almaden Quicksilver County Park.

Ancient Use

The Ohlone peoples, the native inhabitants of the San Francisco Bay Area, mined a red ore for thousands of years. This soft rock, the mineral cinnabar, is a bright scarlet to brick-red form of mercury-sulfide (HgS). The Ohlone used it as a bright red body paint.

The red pigment was a valuable trade item for the local people. Originally, pieces were gathered from streams. But eventually they created a mine by burrowing into a hillside where they found a vein of the mineral.

Later, Europeans would find the remains of a collapsed tunnel with several bodies buried within. The theory, based on oral history, is that the Ohlone were attempting to fracture the rocks using heat. But heating cinnabar produces deadly mercury oxide gas. Once the accident occurred, the Ohlone avoided the “evil” area and the tunnel eventually collapsed.

Mercury Valley

When the Spanish arrived in the area, they used the red pigment for decorating the walls of their missions. In 1845 Mexican calvary captain Andres Castillero convinced the Ohlone to show him where they find the ore. He recognized it at once as Cinnabar and filed a claim to mine the area. It became “New Almaden,” named after the famous mercury mine in Spain.

It was the first workable and richest mercury mine in North America. And it operated from 1847 to 1976. Even after people discovered the dangers of mercury, the mine kept operating. During World War II its mercury was used to make fulminated mercury — The explosive used for detonators that trigger explosive munitions.

The mercury industry was so important to the area that Silicon Valley’s famous newspaper still bears the name, The Mercury News.

Why is There Mercury Here?

If you recall your high school earth science, the United States is part of the North American tectonic plate. And California is where the North American plate abuts the Pacific Plate.

The Pacific plate is being subducted by the North American Plate. And the area where they meet creates the infamous San Andreas Fault. The fault is nearly 800 miles (1300 km) long and at least 15 miles (25 km) deep. The San Andreas is classified as a right lateral (dextral) strike-slip fault. Everything west of the fault is moving toward Alaska. And everything east of it, while also moving north, is doing so at a much slower rate.

It’s this relative difference in speed that causes major earthquakes in California. The average movement along the fault averages between 1.2 – 2.0 inches per year. If current rates of movement persist, Los Angeles will be adjacent to San Francisco in approximately 20 million years.

The meeting of plates creates molten rock within the earth. The volcanoes in my area are extinct. But to the north lie active volcanoes: Mount Shasta, Mount Saint Helens, Mount Rainier, and Mount Hood.

The theory is that molten rock in the area superheated underground water. The water seeped into fissures in the rock near the surface. The water carried traces of mercury, which it deposited into the rock over millions of years. Once cooled, the deposits formed the mineral, cinnabar, which we find today.

The Powder House

I labor a bit on the uphill climb. I’m carrying extra water for the long hike. My destination is a restored building that was used to store the black powder used to excavate the mines. Even after the invention of dynamite, the miners preferred black powder. The dynamite was ill-suited for the dark, wet environment in the mines. The miners worried about it becoming unstable.

Trail to the Powder House

The Powder House was built in 1866

The Powder House

The Powder House was constructed in 1866. More than 150 years before my visit. In 1875, more than 68,000 lbs of powder were used in the mines. In later years it also stored dynamite.

Image of the Powder House from 1895. The surrounding buildings are long gone.

The Mineshafts

From the Powder House I hike to the mouth of the San Cristobal mine. In years past, I was able to enter the mine and walk for a distance underground. I enjoy entering these subterranean relics and am vaguely disappointed to discover a gate guarding the entrance. Begrudgingly, I admit that the gate is probably a good idea. The park is a popular hiking destination — and a lot can go wrong inside an old mineshaft.

A Columbian Black-tailed Deer observes my approach.

Approaching the San Cristobal Mine

The entrance just pops out of the hillside.

The mine was started in 1866

Rails for mining carts run into the distance.

The Hike to the Furnace

I hike on through some beautiful scenery. I can see Mt. Umunhum in the distance. It is the fourth-highest peak in the Santa Cruz Mountains and hosted a cold-war era radar tower (84-foot-high cube). Today it is a preserve with hiking trails and a weather radar installation. The mountain’s name is an Ohlone word meaning “Resting Place of the Hummingbird.” It plays an important role in Ohlone stories.

Mt. Umunhum is in the distance.

Mt. Umunhum hosted an Air Force station during the cold war.

“The Cube” can be seen from the valley floor and throughout the Santa Cruz Mountains. It is the old radar tower.

The Furnace

My next stop is the furnace used to process the cinnabar ore into pure mercury. Along the way I pass an air shaft sunk into the mountainside.

I hike past an old air shaft.

The furnace is an enormous structure. The huge rotary furnace was built in 1939 to supply the demand for munitions during World War II. The cinnabar is heated, releasing mercury gas. The gas flows through a series of condensers that collect the liquid mercury.

The furnace facility is large structure built along a hillside.

The area is gated. So below are some pictures from areas that are not normally open to the public (unescorted). The pictures were taken during a hike I did with a ranger. Accompanying us was a geologist who helped to safely close the mines in the early 1980’s. The park regularly schedules hikes that take the general public within the gates.

I explore the grounds and find an older retort furnace.

As technology improved, the older furnaces were replaced with more efficient ones.

The grounds of the furnace facility

A nearby building housed lockers and showers for the workers.

Showers and changing room.

The office still stands.

The furnace heats the ore and condenses the mercury into liquid sludge.

The resulting sludge is separated to create 99% pure mercury, which is the only metal that is liquid at room temperature.

This stirrer device separates the mercury from the impurities in the sludge.

Here is a picture of how the furnace is today, and another from around 1940.

Furnace in 2022.

Furnace around 1940.

On to the Ghost Towns

I pack up my camera and head for the ghost towns. These are the camps where the miners lived. In my next article, we’ll visit the ghost towns.

Related Articles on NatureOutside

Quicksilver Hike – Hike to the Ghost Towns (Part 2) – Coming Soon

The Tuibun of Coyote Hills (Part 1)

For fun facts and useful tips, join the free Bushcraft Newsletter.

Leave a Comment