Mines, ghost towns, and furnaces: If that doesn’t make an exciting hike, I don’t know what does!

Before the Santa Clara Valley became “Silicon Valley” it could have been called “Mercury Valley.” And I’ve written before about my hikes to the abandoned mercury mines.

Today, I’m headed to two of the ghost towns that surround the abandoned mines. These are the camps where the miners lived.

Ghost Towns

Growing up in New York, I had stereotypical notions about ghost towns. Imagine an Old West town. Tumbleweeds roll down a dusty main street with decrepit two-story wooden storefronts on each side. The hinges of double swinging doors creak in the wind at the entrance to a saloon. And inside, dusty bottles sit on the long bar. Broken chairs, covered in cobwebs, lie on the floor in various states of decay.

Of course, the truth is more complicated. There are ruins from all eras of American history dotting the landscape. And it’s not difficult to find them near my home in the San Francisco Bay Area. In the Santa Cruz Mountains, I can hike through redwood forests to find the remains of sawmills, lime kilns, homestead sites, and logging camps. To the south are abandoned mines and the towns that surrounded them. And to the east are remnants of California’s Gold Rush of 1848. And throughout the landscape are archeological sites of the Ohlone Peoples, the earliest inhabitants of California. Subtle traces remain of village sites, bedrock mortars, and middens.

Spanishtown

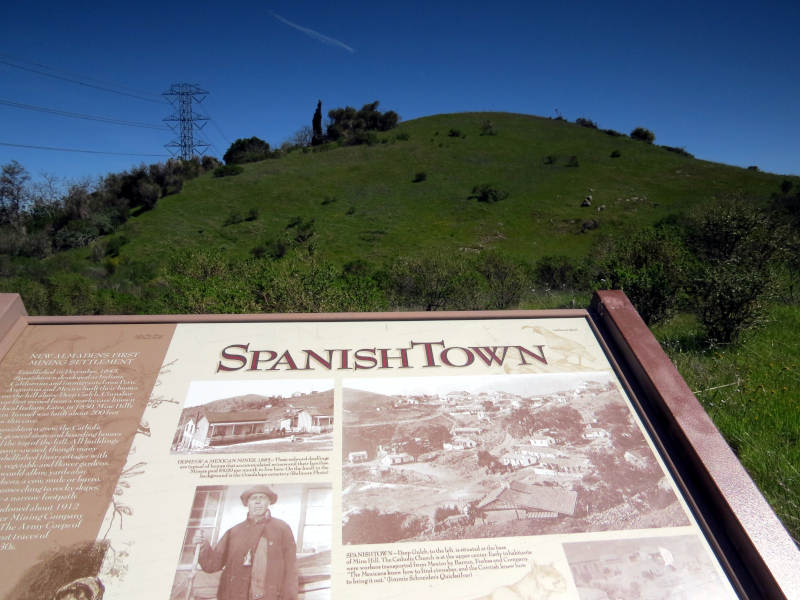

I’m hiking through what was one of the world’s premier sites for the mining and production of mercury. The mines are closed now and the land has become Almaden Quicksilver County Park. Since the ghost towns in this area are well known and readily accessible by the public, Santa Clara County Parks has erected interpretive signs and some fencing around the sites. Many other ghost towns in the area are protected by their anonymity or the need to hike to remote locations.

It’s a gorgeous summer day and the sky is a dazzling Pacific blue.

Looking into Deep Gulch.

I pass the ruins of a relatively recent building.

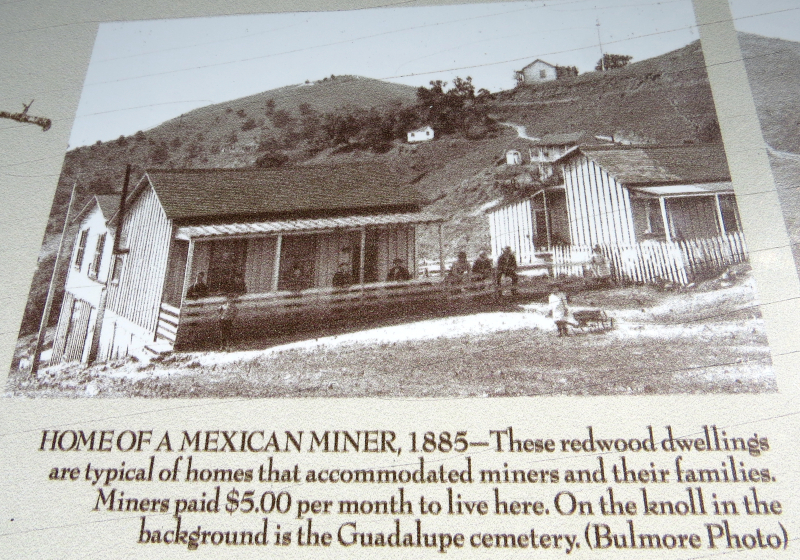

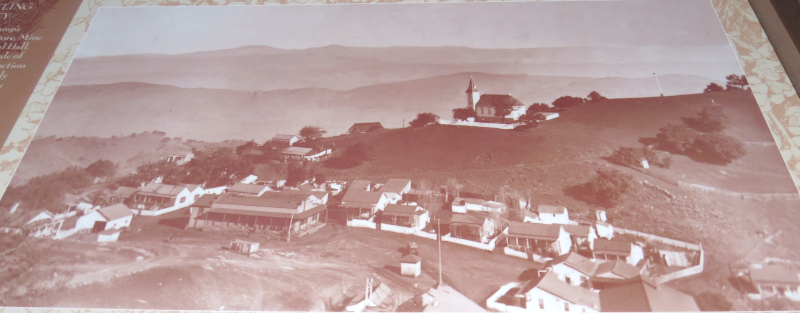

I arrive at the site of Spanish Town. The structures are gone and a historical marker denotes the site. The town was founded in 1845. It was home to Native Americans, Californios, and immigrants from Peru, Argentina, and Mexico, who came to work the mines. As the population grew, they built a Catholic church, general store, and boarding houses. Families lived in cottages with vegetable and flower gardens. They raised livestock in larger yards. All the structures were owned by the mining company.

The town was abandoned around 1912 when the Quicksilver Mining Company went bankrupt. The Army Core of Engineers removed most of Spanishtown in the 1930s.

Looking at the picture, with the hill in the background, it seems an entirely different place.

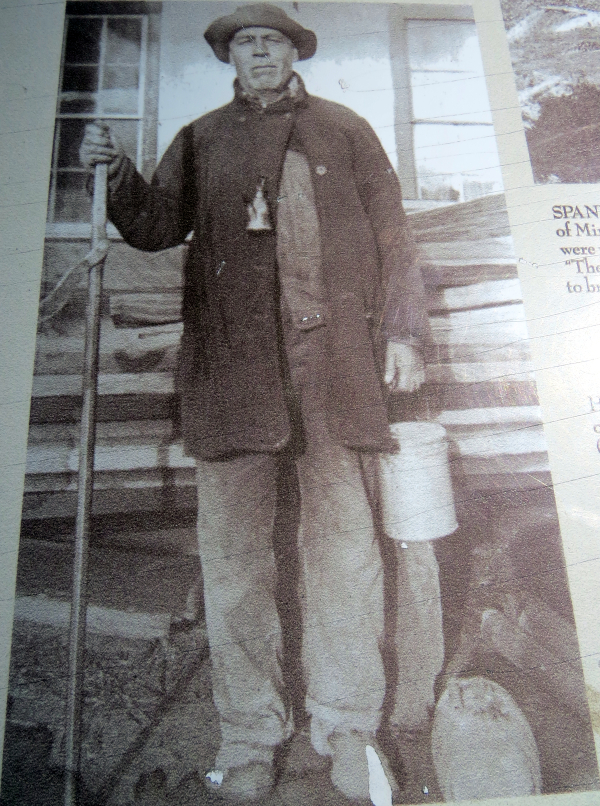

The historical marker also shows a picture of a miner. The miner is Patricio Avila. A miner’s lamp that burns whale oil hangs on his coat. He carries a drill, lunch basket, and water bucket. Like outdoorsmen of today, he dresses in layers. This allows him to accommodate the temperature difference between the surface and inside the mine.

Photograph of a miner from 1890

I shake my head at the thought of descending into the mine in the 1890’s and working in those conditions.

English Camp

As I make my way to English Camp, I pass California Poppies, California’s state flower. I’m dazzled by the contrast between the green hillsides and bright orange flowers.

California Poppy (Eschscholzia californica)

English Camp was once a mining community of around 1,000 men, women, and children. It was founded in the early 1860’s by immigrant miners from Cornwall, England. Cornwall has a history of mining that dates back to the Bronze Age (around 2150 BC).

Very few structures remain: The foundation of the schoolhouse, the foundation of a residence, and a map-house/office. A later structure remains from the Great Depression (1933 – 1942), when the Civilian Conservation Corps used the town as a base of operations.

English Camp, founded in the early 1860’s

Nearby are the remnants of a “map house” and office. This structure was built in the 1940’s beside the original cabin that housed the mine’s paperwork. After mining operations ceased, the maps and mining records were donated to nearby Stanford University.

Map House

Is History Spooky?

It’s hard to describe the feeling of walking through these silent ruins. It reminds us that things were not as we know them today, and will likely be different in the future. It reinforces the idea that our time on Earth is brief. And we will most likely be known from our works of creation or conservation.

There is no English word that expresses this “sense of history.” So I recommend you experience it for yourself. See if you can find a “ghost town” nearby that you can visit.

Related Articles on NatureOutside

Quicksilver Hike – Hike to the Mines (Part 1)

Hike to Skeleton Grove (Part 1)

For fun facts and useful tips, join the free Bushcraft Newsletter.

Leave a Comment