An obscure mark on a hundred-year-old map leads to an off-trail adventure…

I want to share an adventure with you. It starts with my friend, Kurt. I first met Kurt when he joined a 9-mile hike I led for California State Parks. Thereafter, I would see him on the trail from time to time. He is hard to miss. Kurt has a distinctive white beard and hikes with his hair tied back under a bandana. His understated backpack sports a Wilderness First Responder patch with a ham radio attached high on one shoulder.

Kurt is a fun guy to hike with. He covers long distances without flagging and has an intimate knowledge of the area. He hikes with quiet competence and is an all around cool dude.

One day as we were talking, I lamented my lack of local knowledge. Surely there must be “hidden treasures” shrouded by the forests on the western slopes of the Santa Cruz Mountains. It was then that Kurt offered to take me to the caves.

Maps are living documents

The map is not the territory.

– Alfred Korzybski

Most of us have heard this expression. Hikers learn it soon enough. The map is only a representation of actual land. And it is often imperfect! Through experience I have learned that if the map and the land disagree, believe the land!

Maps are living documents

– Me

Have you heard this expression? Probably not, because I just made it up! 🙂

I always believed that newer maps were better. I took it on faith that more recent maps had added detail, were more accurate, and were made using more sophisticated techniques. The evidence was right before my eyes. I could look at my newer 7.5 minute topo maps and easily pick out details that were not on the older versions.

But I never stopped to consider that it also works the other way. Just as features can appear on a new map, features can also disappear! This may be because the feature (like a building) no longer exists. But it also happens for political, economic, or social reasons. Kurt understood this. He realized the value of old maps.

Cryptic Markings

The map was from 1912. Night had fallen outside my window as I stared at the glowing computer screen in increasing frustration. I combed over the digitized terrain several times, knowing where to look but still not seeing. Finally, I discerned a scribbled notation.

![“Caves in Sumit [sic] Rock” (Magnified 200% and sharpened)](https://www.natureoutside.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Map-MarkingCroppedEnhanced200x.jpg)

“Caves in Sumit [sic] Rock” (Magnified 200x and sharpened)

Even enhanced, the cryptic marking is barely legible. If I had stumbled upon it without warning, my eye would have glossed over without pause. But Kurt recognized its significance.

Here is the clever part. Kurt then chose features on the 1912 map that exist today. He used them to register the 1912 map onto a modern digital terrain map. At that point, he was able to approximate the GPS coordinates for the “Caves in Sumit Rock.”

Planning the Adventure

Kurt had already visited the caves. So we had good GPS coordinates for them. But many times the quickest way to your destination is not a straight line!

The caves were in a remote area with no trails or roads. The caves themselves were in the face of a steep incline, almost a cliff. We had two choices to reach them. We could hike in using a little-used fire road and then climb up. Or, we could hike a trail that led to a ridge connected to the one with the caves. The road option looked attractive, but entailed a steep climb in difficult terrain. So we chose the second route. By doing this we could climb to the elevation of the caves on the maintained trail. Then we could hug a contour line of the ridge all the way to the caves.

But this approach required considerable bushwhacking to reach the caves. We would travel in dense forest and we had to be careful not to descend below the level of the cave entrances. Climbing up to the caves would be a miserable experience. But if we were too high, we could find ourselves peering down a steep cliff face at them. As long as we maintained an accurate GPS fix in the forest, we would monitor our elevation and arrive at the caves along a contour line, at their level.

After visiting the caves, we would depart the area by descending through the forest to the fire road. The road would return us to our trailhead. In all, it was a 9-mile roundtrip. But because of the off-trail travel we allowed extra time for our journey.

Moving through the undergrowth

The sky was a piercing blue as we left the trail. We would not see it again until we reached the caves. What started as a chilly morning became a comfortably warm day. We were already warmed by the steep climb needed to reach our present location.

We set out across the hillside through an open forest of Redwood, Tanoak, and Douglas fir. A dry, earthy, smell filled our lungs and the air temperature dropped noticeably under the forest canopy.

I anticipated easy going through the open forest. But I was mistaken! The duff made for treacherous footing and a number of steep ravines creased the hillside. Each time we encountered a ravine, we had to carefully descend and climb the opposite side. For many, we detoured uphill to find a shallow place to cross. But each time we had to be mindful of our elevation with respect to the cave entrances.

Huckleberry bushes were a surprising obstacle. The woody shrubs stretched their limbs like giant octopi. Too dense to walk through, we ducked around them. Their springy limbs scratched at our clothes and searched for our eyes.

Smaller, shrubby Tanoaks posed problems similar to the Huckleberry. Too dense to walk through, we diverted around them.

Fallen trees proved to be another problem. Tanoaks we could scramble over. But redwoods and the larger Douglas firs were a different matter. More detours and a little climbing kept us on our way.

I disturbed a small Coast Gartersnake, no more than 4 inches long, sunning itself on an exposed tree root. I carefully stepped over it as we proceeded on our way.

We expended a prodigious amount of energy hiking through the forest compared to on the trail. Just to remain balanced on the steep hillside burned calories. With the benefit of GPS, we were able to track our progress toward our goal. But imagine traversing these trail-less woods with no end in sight. How did the early pioneers do it?!! It must have taken tremendous perseverance to explore this land beyond the well-established trails.

I employed a trick I often use when bushwhacking. I followed deer trails. The deer want to expend energy as efficiently as possible. They are not likely to change elevation without good reason. So, we found a deer trail at an acceptable elevation and followed it like a high speed railway. When we came to junctions I would cast ahead for obstacles and select the deer trail heading toward our destination. This sped our progress considerably and prevented large excursions uphill or down.

Descent to the caves

The GPS showed we were nearing our destination. But we were too high! Angling downhill, we reached what seemed to be an impenetrable wall of brush. But Kurt led us through a break in the foliage and we found ourselves on the side of a steep incline with the cave openings before us. The footing was unsure, and my dislike of heights kicked into overdrive. Fortunately, there wasn’t far to go.

Approach to the caves. You can see the entrances to the top, middle, and bottom caves diagonally from the upper left to the lower right. Note the steep hillside we have to descend.

Here is a closer shot of the cave entrances.

The top cave entrance.

The middle cave entrance

The bottom cave entrance

As we negotiated the slope, I remembered the first scenes from Raiders of the Lost Ark. The notes of the theme music were sounding in my head.

Band-tailed Pigeon

As we emerged from the brush, I heard the distinctive call of the Band-tailed Pigeon (Patagioenas fasciata). We had heard it calling several times in the forest. To me, their bass “coo” sounds much like a stereotypical owl.

Picture a large (and I mean large!) pigeon colored like a Mourning Dove. Books say they are smaller than the American Crow. But when I see one it invariably looks huge, like a pigeon with a personal trainer. Mostly I see solitary birds foraging for seeds on the forest floor. Occasionally I see one perched high in a tree surveying the forest below.

As we made our way down to the caves, we saw a large band-tailed pigeon perched on a dead tree in front of the middle cave. As we drew near it flew off into the forest and we did not see it for the rest of the day.

Top cave

The three caves are arranged diagonally across the hillside. You can climb a narrow ledge up the hillside to reach the top cave (pictured above). I was game to try the ledge, but Kurt was not interested. He said he had been up to the cave and there was not much to see.

So, we continued gingerly to make our way down to the middle and bottom caves.

Middle Cave

The middle cave is my favorite. It is a large chamber carved into the sandstone hillside. Orange/brown minerals paint the sides with swirls. A “skylight” punctures the roof, allowing light to enter from in front of the opening to the top cave.

There was a large opening in the floor to the right of the entrance. The sloping passageway leads through the roof of the bottom cave.

Skylight leading to ground in front of the top cave.

Part of the back of the cave. Colored swirls are interrupted by tafoni-like holes.

A hole in the cave floor leads through the roof of the bottom cave.

Trying for shots that will do justice to what we we see

Swirls of orange/brown may be caused by iron-containing minerals. Geology is one of my weak spots.

A close-up of the swirls on the walls at the back of the cave

Mystery Footprints

While the walls were terrific, the cave floor was astonishing! Comprised of sand worn from the walls by years of erosion, it was smoother than the most perfectly groomed sand imaginable. But there were no signs of a broom-stroke or any other disturbance. It looked pristine, like we were the first humans to lay eyes on it.

I rushed forward eager to see if the sand provided clues to the cave’s inhabitants, if any. It did not disappoint! I stepped delicately across the sand onto a rock in the middle of the cave. I treaded carefully to disturb the floor as little as possible.

Animal tracking in the cave

From my vantage point, I had a 360-degree view of the cave floor. Sure enough, the floor told a story. Below a dead tree at the cave’s opening was a large amount of bird droppings. It was the same tree where we saw the Band-tailed Pigeon. It appeared this was the pigeon’s home.

There were quite a few bird tracks in the area. But were they the pigeon’s? It was difficult to tell, but they looked a little too small to my eye.

Bird tracks on the cave floor

A close-up of the bird tracks

But there also appeared to be a track of a much larger bird. But I could only find one track, which is a poor sample size for an identification, given my lack of expertise. Yet, it looked strangely familiar.

This also appears to be a bird track. But it is much larger (about 3 inches) and deeper than the others.

I also found this trail on the sandy floor. The length of the track is about 14” total. It is about .25-.5” inches wide. It appears to connect two holes in the sand. Any idea what this is?

An unidentified trail

The cave left me with many questions to further my tracking education.

There was no ambiguity about the last set of tracks. It appeared that a raccoon visited the caves regularly. The trail ran from the entrance down into the hole in the roof of the bottom cave.

The tracks had the alternating diagonal overstep pattern characteristic of raccoon.

A close-up of the raccoon tracks. The left track is the rear-left and the “hand-like” track on the right is the right-front.

One thing that was missing was any sign of human disturbance. I have become so used to the signs of humanity (trash, graffiti, etc.) that it always surprises me when there are none. The only indication that man had ever visited the caves was on the hillside near the entrance. Someone had carved his initials into the sandstone with the year “1951.”

Bottom Cave

Entrance to the bottom cave. The hole in the ceiling leads inside the middle cave.

Kurt leads the way.

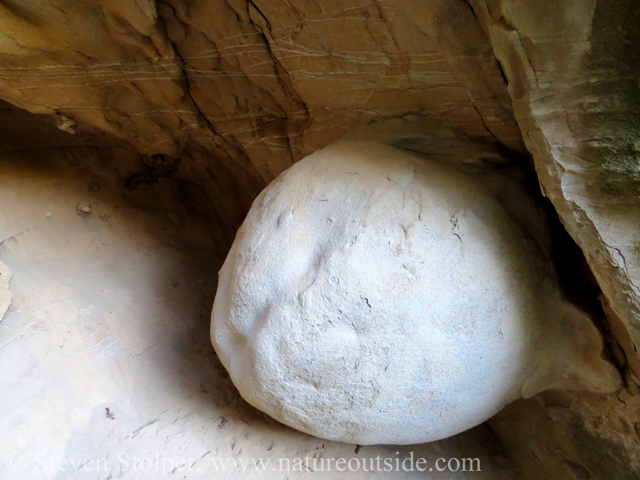

The bottom cave had a surprise in store for us. A giant sandstone globe!

An amazing sandstone globe

A closer look at the globe and the veins of quartz in the wall above.

I suspect water must have eroded around the sandstone and time and the elements did the rest. The rock was more than 3 feet in diameter and must have weighed more than 2,000 pounds. I have never seen anything quite like it.

After lunch, we took another look at the bottom cave. We found what appeared to be a raccoon latrine below the opening leading to the middle cave. After snapping a few more photographs we headed back to civilization.

Back wall of the bottom cave

Kurt in front of the bottom cave

Let Your Map be your Passport

You can open a world of adventure by letting old maps be your guide. I came away with a newfound appreciation for what old maps have to tell us. What other forgotten wonders are out there waiting for us to rediscover?

Have you ever used an old map to find a “lost treasure”? Tell me about it in the comments below.

Other Trips on NatureOutside

An Air Disaster and Historical Hike

For fun facts and useful tips, join the free Bushcraft Newsletter.

Great story Steve. I did a little investigating using J.C. Fremont’s map of his explorations around south-central Oregon and was able to find several of his camping spots. Fortunately I also had his Journal notes that contained some, often suspect, lats and longs and descriptions of the surroundings. I wrote a little ebook about how to combine the old map, the journal entries and new maps and GPS to tack along the journey.

If you would like to pursue this, the map, the journal and my ebook can be found by registering for the Discover Club (free) at http://www.exploreemag.com – click the Discover Club menu item at the top.

Now you have me thinking about the original land survey maps that often had notations like the one you found. Years ago I was peripherally involved in a project to digitize some of those maps and link them to the associated notes – I don’t recall what might have happened with that project. I wonder what treasures Google will ofter.

Jerry — It sounds like you had a similar experience piecing together Fremont’s map and journals. I do think that the early survey maps have stories to tell. Many state university libraries now have map collections already digitized. This may be a good place to start future adventures.

This is fascinating. I’m a geology major, so i’ve got people on this.

I love the obviously layered colors of sediment layers that once sat underwater. Those circles interrupting the bands are drop-stones that fell and squished craters into the soft seafloor, but i’m not sure about the wave patten on top of them. The whole thing has been warped with ductile deformation, but not as much as i would have thought with it being on a mountain like that. Its preserved pretty well.

Either way, its eroding tunnels and very smooth so it shouldn’t be a sandstone. It behaves like a limestone/dolomite which are the most common cave-forming rocks. Because the three caves are aligned on one slope, it seems like the bottom/left of the cave is a much sturdier rock type and has kept this cave pretty small. Sandstone is insoluble so while there is sand coming from it, its not sandstone. The fine soft sand you described makes since because what would physically erode from a limestone cave is very fine and should not contain the hard quartz that makes beach sand so brutal.

You were correct on the giant rounded rock. It either fell inside and got stuck or was very lucky to be eroded around. Looking at it again, i favor it being from an outside source. The color is off in the photo, and its too durable at that size to be THAT lucky.

Those quartz veins are in everything mountainous, but I’m always happy to see them. Very pretty.

Sarah, thanks for the fascinating analysis! I appreciate you sharing your geology knowledge with us.

Very cool! This inspired me to go find some old maps of the area I live in. Found a good one from 1896 on the USGS site. Now to peruse…

Corey — Terrific! Let us know what you find.