Several NatureOutside readers contacted me this month, asking about what to do if they get lost while hiking. It’s not a quick answer. And I want to give good advice. So here are my thoughts on what to do if you get lost in the wilderness.

This article contains affiliate links.

Why do People Get Lost?

Once when I was lost I saw a policeman and asked him to help me find my parents. I said to him, “Do you think we’ll ever find them?”

He said, “I don’t know kid. There are so many places they can hide.”

– Rodney Dangerfield

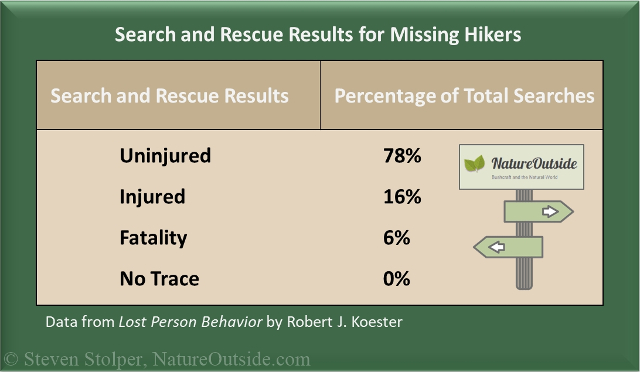

Despite Rodney’s joke, getting lost in the wilderness is no laughing matter. In fact, many survival situations start out as navigational errors. According to the 2008 book, Lost Person Behavior, becoming lost accounts for 68% of searches for missing hikers. This is the leading cause of SAR efforts involving hikers. So for each trip, getting lost should always be high on your risk assessment.

Data shows that hikers often get lost at decision points (56%)1. These are trail junctions and intersections with unmaintained trails, game trails, social trails, and drainages. It’s a common error to head the wrong way on a trail at a junction. But sometimes hikers will leave the trail without even noticing. In this case, it’s inattention that creates peril. (Please don’t ask me about the time I guided a group of elementary school students into a dead-end canyon on a deer trail.)

For hikers, here’s data from search and rescue efforts in the United States1:

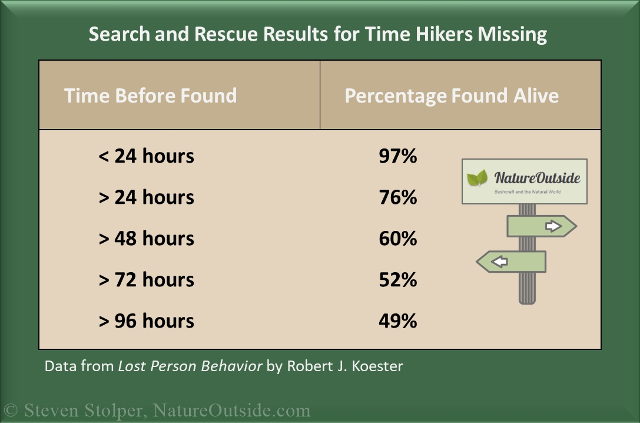

You can see that survivability declines the longer you are missing. So the actions you take after you discover you are lost are critical.

Stay Found

When it comes down to it, the best thing you can do is stay found! Notice landmarks as you hike. Pay attention to the trail and your surroundings! Check the map often. And if the terrain and the map disagree, believe the land!

Don’t take shortcuts, and don’t cut switchbacks. These increase the likelihood you’ll miss the trail.

As you hike, glance behind you periodically. You’ll see what the trail will look like on your way back.

Finally, learn land navigation. This includes using a map and compass, map and GPS, dead reckoning, and other important techniques. Then practice, practice, practice.

Let Someone Know

In the lower 48 states, searchers are statistically likely find you within 72 hours of when they start searching. But there’s a catch. They need to know you’re missing!

The best thing you can do when you hike is to leave your plans with a loved one. Tell them where you are going and when you will be back. Give them a phone number to call if you don’t check-in with them at the proper time. This phone number can be 911, or the law enforcement organization in the area where you’re going. Many hikers have been saved using this simple procedure.

I like to leave the following information with my loved one before I hike:

- Where I’m going

- My destination and route

- Time when I will return

- Phone numbers to call if I do not return by that time

- A description of what I’m wearing

- How much water I have

- How much food I have

This person needs to care about you enough to act if you don’t return on time. Several tragedies have occurred because the trusted person became distracted and never called for help. Choose the person wisely and give them explicit instructions for what to do if you don’t return on time.

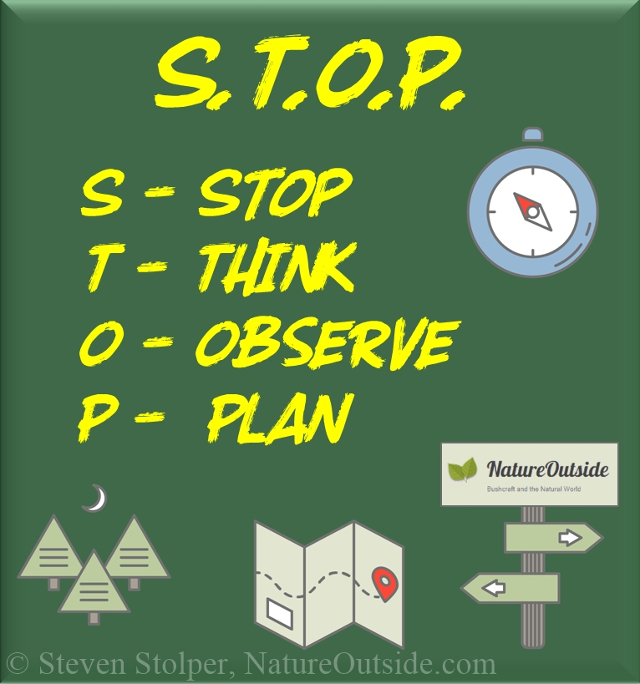

STOP!

What do you do when you’re hiking along and suddenly you realize you are lost? You STOP!

S – Stop walking

It’s important to stop walking the moment you realize you’re lost. At this point, you are closest to the last point you knew where you were.

Many adults will panic and quicken their pace. But often in the wrong direction! This makes it more difficult for searches to find you. There have been several cases where hikers were found miles from where they were supposed to be because they pushed on in a blind panic when they realized they were lost.

T – Think

In the “good ole’ days,” survival instructors would tell you to stop for as long as it takes to smoke a cigarette. Now that we know the unhealthful effects of smoking, I suggest you stop long enough to drink some water and have a snack. The idea is to let the shock of being lost subside. You need to lower your heart rate so you can think clearly.

You should ask yourself the following questions:

- Do you know where you are on the map?

- Do you know where you went wrong?

- Can you backtrack to your last known position?

O – Observe

Examine your surroundings. What can you learn about where you are?

- Can you see the trail?

- Do you see a landmark you recognize (use your map)?

- Can you backtrack your footprints?

- Can you see other human footprints or tire tracks?

You can explore your surroundings without getting further lost. I carry a small amount of bright pink surveyor’s tape. I can hang it from a high tree branch and it will be visible from a great distance. Then I can strike out in a direction to explore, being careful never to lose sight of the tape hanging from the tree.

I return to the tape (the point I realized I was lost) and try a new direction. In this way I can explore a wide area without worrying that I’ll wander farther from the trail.

This is an old technique. In the days before surveyor’s tape, frontiersmen would hang moss in the tree. They used species that do not normally grow on trees, so it was easy for them to spot.

P – Plan

Make a plan. Can you backtrack? What direction should you travel to find a place you’ll recognize? Do you see a long linear feature on the map you can intersect without fail? Is there a place nearby with a better view?

Don’t move unless you have a plan.

Call or Text

If you are lost, it is worth trying to contact authorities using your cell phone. But that only works if your cell phone battery is charged. Make sure you fully charge your phone before you begin the day.

To preserve battery, always turn off your phone or put it in Airplane Mode at the trailhead. If you use your phone as a camera, Airplane Mode still allows you to take pictures. Many wilderness regions don’t have cell coverage. And your phone quickly discharges its battery searching for signal. So train yourself to take this precaution at the start of your hike and your phone will be available when you need it.

You can sometimes find cell coverage by hiking to higher ground. But don’t risk yourself to do it! Also, do not get yourself further lost in the process.

Turn on your phone (or take it out of Airplane Mode) and try calling 911. If you cannot make a voice call, you may still be able to send a text message. Send a text message to the person who has your trip plan. Also send a text message to 911.

The reason you text the person who has your trip plan is because not all municipalities offer text-to-911 service. I believe that right now most don’t. So it’s more likely your loved one will receive your message than 911.

Your message should contain:

- Your name

- The name of the park and the trail you were on or last known position

- Request for help

- The problem: You’re lost

- Any landmarks you can see

If you’re lucky, a text message will get through even if there is no voice service. But don’t count on it.

Once you do this, keep your phone on (in regular mode) unless authorities give you different instructions.

Draw Attention to Yourself

Draw attention to yourself to increase your chance of being rescued. A rescue whistle can really help. If you’ve ever yelled for any length of time, you realize that your voice quickly becomes hoarse. But you can blow a whistle all day! Three blasts from a whistle means HELP! Hold each blast for a count of four. Stay silent for a count of four. Then issue the next blast. After a cycle of three, stay silent for a short time. Listen for a response. Searchers may answer with one long whistle blast.

A signal mirror is a useful tool in open country. A snall 2”x3” mirror is easy to carry and lightweight. Flashes from signal mirrors can be seen for more than 20 miles. They grab peoples’ attention from as far away as 15 miles. Makeup mirrors or the reflective hologram on a credit card will do in a pinch. Use your ingenuity. If you don’t see an aircraft, vehicle, or people to flash, then flash the horizon in all directions from time to time.

A signal fire is a special fire that sends smoke high into the air. But only build one if you know what you are doing! Burning to death in a forest fire is a terrible way to be rescued.

A signal fire is built more than two feet above the ground. You lash a frame together to hold the fire. With dry burning material covered by green plant material, it produces a lot of smoke. The raised fire creates a convection current that punches smoke high into the air. But strong winds and a heavy tree canopy can limit its effectiveness. WARNING: Only use a signal fire if you know what you are doing!

If you hike a lot, consider investing in a Personal Locator Beacon (PLB) or a satellite phone. Note that a PLB is different from the commercial subscription products. The PLB hardware is usually more expensive, but the link to the government satellite network is free (it’s a public service). There are legal ramifications to misusing a PLB, and you need to read the training materials that come with it. My favorite PLB is the ACR ResQlink. There are several models to choose from, including one that let’s you send a routine “I’m OK” message.

If you hike often in remote areas, a satellite phone may be a good choice. However, I have never used one so I cannot comment on their utility.

Hug a Tree

If you can’t find your way back, stop moving. You may be going further in the wrong direction. Studies have shown that people tend to walk in circles when they don’t have navigational references. Don’t waste energy walking in circles.

Education programs teach children to “hug a tree.” This program has been credited with helping rescue children lost in the wilderness.

The cold hard fact is, if you don’t have a plan to rescue yourself, you should plan to spend the night in that location.

If you carry the right equipment and have sufficient training, an unplanned night in the wilderness is not a survival situation. It’s just an inconvenience. A good survival class will help you learn the skills you need to spend an unplanned night out.

Stop for the Night

Don’t try to hike at night. I repeat: Don’t try to hike at night.

Even with a flashlight or lightweight headlamp , it’s easy to get injured hiking at night. The terrain is uneven and it’s difficult to see hazards. Make no mistake: Being injured and lost is worse than just being lost.

You also need to stop early enough to find/build a shelter. Allow at least two hours if you have shelter materials in your pack. If you need to build a shelter from natural materials, stop at least three hours before sunset. If you do not know the time of sunset, use the hand trick to estimate when the sun will set.

Stay near water if you can. But set up shelter far enough from the bank that you will be safe from a flash flood. Do not shelter in the bottom of a canyon. Cold air sinks and you will be less comfortable than sheltering a little higher. Seek natural shelter like trees or rock overhangs to get out of the weather.

Taking a good wilderness survival class will teach you what you need to know to spend an unplanned night outdoors. I teach a free class for California State Parks in the summertime. It’s a public service and we give the class several weekends each year.

Carry Extra Food, Water, Clothing, and Shelter

Always carry extra water, food, and warm clothing. It will make the night comfortable if you are lost outdoors and need to spend the night. This is the minimum you will need to be comfortable. I also carry a lightweight tarp and other equipment I know how to use.

Hike with a Friend

There are several advantages to hiking with a buddy. Two heads (and arms and legs) are better than one. And there will be two sets of loved ones calling authorities if you’re overdue.

Just don’t become distracted talking and miss the trail. 🙂

It’s always better to hike with a buddy!

Conclusion

Getting lost is the top reason for search and rescue efforts to find missing hikers. The easiest thing to do is to “stay found.” But if you get lost, STOP! Carry enough with you to draw attention to yourself and to be comfortable if you need to spend the night.

Everyone get’s lost. Even the famous frontiersman Daniel Boone said:

I have never been lost, but I was bewildered once for three days.

– Daniel Boone, when asked if he had ever been lost in the wilderness

It’s what you do after you discover you’re lost that really matters.

Have you ever been lost? Tell me about it in the comments below.

References

- Lost Person Behavior, Robert J. Koester

- Title photo by Micah Hallahan on Unsplash

- Slider photo by Oziel Gómez on Unsplash

Related Articles on Nature Outside

3 clever tricks to use the sun while hiking

How to Choose a Wilderness Survival Class

For fun facts and useful tips, join the free Bushcraft Newsletter.

Helpful, thoughtful article. I’ve never been lost for long but it isn’t a good feeling. I have a friend who works search and rescue in the Smoky Mountains. She has articles on what to carry on every hike to keep you safe, hiking with your dog, etc. Her name is Nancy East (Hope and Feathers) on Facebook. You might enjoy some of her thoughts.

Thanks, Mel! I’ll take a look at Nancy’s writing.