Sometimes you Just Gotta’ Get Away

After a long week at work, I was excited to get a few days off to go hiking. My plan was to hike and camp for two days and nights in Yosemite National Park.

The first day, I arrive at the park around noon. My plan is to hike to Lembert Dome, which overlooks Tuolumne Meadows. From Lembert Dome, I will continue to Dog Lake to enjoy a relaxing swim before returning to the trailhead. The entire hike would be less than five miles with about 900 feet of elevation gain – a great hike to help me acclimate to the altitude.

Tuolumne Meadows is a beautiful sub-alpine meadow northeast of Yosemite Valley. It’s early September, and the Tuolumne River meanders across the valley under a piercing blue sky. The meadows lie at an elevation of 8,600’ (2,600 m). So you need to keep a weather eye out for afternoon thunderstorms. But this day looks perfect.

Lembert Dome

Lembert dome towers almost 900 feet above the valley floor at 9,449’ (2880 m). It only looks domelike from certain angles. For it is truly a roche moutonnée, a rock formation shaped by the passing of a glacier1. The ice moved generally westward through the area, creating a smooth sloping eastern side and a rough, “plucked” cliff face to the West. So you do not have to be a technical climber to reach the top. You simply walk around it and slog your way up the sloping side.

Lembert Dome as seen from Tuolumne Meadows

I have wanted to climb to the top of Lembert Dome for several years. So I set off at a brisk pace from the trailhead. Along the way, I stop to contemplate a series of bedrock mortars left by the original inhabitants of the valley.

Bedrock Mortars near Lembert Dome. Please be respectful and do not walk or stand on them.

According to the National Park Service, the Miwok and Paiute used the Mono Trail through Tuolumne Meadows as a trade route between the eastern and western slopes of the Sierra. Archaeological deposits appear to confirm accounts that eastern Paiute and western Miwok stopped here to camp and trade during the summer2. They traded animal pelts and acorns for pine nuts and obsidian3.

Sites like this one always fuel my imagination. I try to imagine what the place might have looked like hundreds (or thousands) of years ago. I’m careful not to walk on the mortars, as a sign of respect to the people who once lived here, and their descendants.

Climbing through the Pines

Hiking through lodgepole pines growing in duff on the granite

The trail climbs steadily upward through a forest of lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta).

Several times I think I see movement out of the corner of my eye. Something small, on the ground, is shadowing me in the forest. When I whirl to look, it’s gone. When it happens a third time, I quicken my pace and put distance between myself and the disturbance. I then stop and silently creep back to where I sensed the movement. Finally, I see this adorable creature:

Alpine chipmunk (Tamias alpines)

I’ve never before seen an alpine chipmunk (Tamias alpines). So there is a momentarily thrill of seeing an animal I do not recognize.

Alpine chipmunks are native to the high elevations of the Sierra Nevada. They are usually found above 8,200 feet, higher than any other chipmunk species. They live in rocky areas such as rock-bordered alpine meadows, talus slopes, and among scattered boulders in lodgepole pine forest. Its high altitude habitat and pale coloration are clues I use to identify the animal using a field guide.

Alpine chipmunks eat seeds of sedges, pines, and other alpine plants. They also dine on forbs, grasses, berries, and even some fungi.

The chipmunks hibernate from October to June in order to escape the extreme Sierra snows. During warm summer days they shelter under rocks to thermo-regulate.

The animals appear adapted to cooler temperatures found at the higher elevations. As a result, they may be threatened by global warming. The Center for Biological Diversity reports that in Yosemite National Park, the alpine chipmunk has shifted its territory upward by more than 2,000 feet during the past 90 years. As temperatures continue to climb, the alpine chipmunk is in danger of running out of habitat.

Lembert Dome

Spiraling up the perimeter of the dome, the trail splits off onto a branch that climbs up the spine of the edifice. Eventually, I emerged from the pines onto bare granite.

Breaking out onto the ridge. Notice the two people walking and one sitting just above the base of the dome.

The steep sides of the ridge

At this point, I’m left to find my own route. Bypassing the peak, I circle around its steep sides until I find a more gradual path to the top. The view is spectacular! My pictures do not do justice to the sense of height you feel walking on the stark granite bluff.

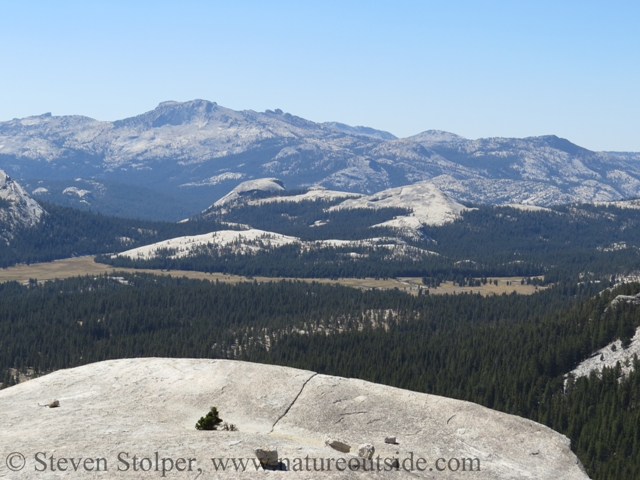

Looking around from the top of Lembert Dome

The Top of Lembert Dome. I imagine the husband taking the photo saying, “Just another step back, Honey…”

The view from Lembert Dome

There are a number of other hikers on the dome, relaxing and drinking in the amazing view. Immediately below us are the meadows, irrigated by the meandering Tuolumne. Despite the intense sun, a chilly wind gusts around us as it sweeps down from the higher peaks.

View toward Tuolumne Meadows

Looking south from Lembert Dome

Tuolumne Meadows Below. Possibly smoke from a potential forest fire (upper left).

Gorgeous Views

The meadows below

Here is a picture looking back from the dome’s western plateau:

Looking back on Lembert Dome. Notice the people relaxing.

Dog Lake

Dog Lake lies about a mile beyond Lembert Dome. It’s a large picturesque lake surrounded by sedge and lodgepole pine. The lake is shallow, which makes it relatively warm and inviting – perfect for wading or a refreshing afternoon swim.

Tranquil Dog Lake

The lake is wonderfully clear and shallow. Notice man in water (at left).

The Ice Bucket Annoyance

In the pictures above, you may notice a man in his 50’s on the left-hand side standing in the water. His wife is standing on the bank with a hand-held video camera. He is filming a version of the Ice Bucket Challenge while on vacation.

A viral internet phenomena, the Ice Bucket Challenge involves dumping a bucket of ice water over your head and making a donation to the ALS Association. You then challenge others, by name, to do the same. The proceeds help fight amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Lou Gehrig’s Disease) and is a cause worthy of attention.

However, this guy is driving some of us hikers crazy! Speaking at high volume in a Midwestern accent, he acknowledged by name all the people who challenged him to join the craze. I couldn’t help but notice how many people wanted to see a bucket of ice water dunked over his head. Then with a flourish, he ducks his head underwater and spends another couple of minutes commenting on the cold water.

But he keeps flubbing his lines! So time after time, take after take, those of us relaxing on the bank are subjected to a high pitched, nasally, academy awards acceptance speech. In my relaxed, welcoming state of mind, I easily memorized his lines despite myself! Bemused, I glance around and catch the eyes of a group of young hikers from the UK. We exchange glances like people trapped waiting in a doctor’s office.

Climb High Sleep Low

I return to the trailhead without incident and set out for my campsite. I’m staying at a developed campground at 4,900’ (1,500 m). There’s an old maxim among mountaineers, “Climb High Sleep Low”. This helps your body acclimate to the altitude. During sleep, respiration decreases, exacerbating any symptoms caused by altitude. Sleeping more than 3,500 feet below my hiking elevation was part of my plan to adapt to the local environment.

For tomorrow, I plan to hike the 16.4-mile round trip from Yosemite Valley to the top of Half Dome.

Further Reading

-

Yosemite National Park: A Natural History Guide to Yosemite and Its Trails with Map, Jeffery P. Schaffer, Wilderness Press, 1999.

-

William E. Colby, Jean (John) Baptiste Lembert–Personal Memories. Yosemite Nature Notes 28.9 (September, 1949): 114.

For fun facts and useful tips, join the free Bushcraft Newsletter.

Leave a Comment