Tanoak Acorns

For me, the end of summer is signaled by the start of the acorn harvest. True oaks (Quercus) and Tanoaks (Lithocarpus) in my area produce a bountiful crop of acorns. Nutritious food literally falls from the trees!

Acorns!

Indigenous peoples around the world used acorns for food wherever they occur. They have a rare combination of nutrients that today we would call a “superfood.” Acorns contain natural preservatives making them easy to store – the ideal food to sustain native peoples through winter.

Good for the Body, Good for the Soul

I also use acorns for food. Sometimes I prepare a traditional mush, other times I use acorn meal to bake my favorite Orange-Acorn bread. Processing acorns into food gives me a great deal of pleasure. And I think you will enjoy it, too.

The process of selecting, gathering, processing, and cooking acorns connects us to our environment in a way that is missing from modern life. We experience the heightened sensitivity and focus of the gatherer. We gain the satisfaction of producing food from nature using our own ingenuity. But most importantly, we begin to understand what it is like to depend on nature for our next meal.

It’s Easier than You Think

When I meet people who love nature, they often express a deep desire to harvest acorns for food. Many think it’s difficult. They have heard stories about grinding and leaching and days of labor. Others simply don’t know where to begin.

I will share my method of processing acorns into food. The method is simple and can be accomplished with a few household utensils. It works best for small amounts and is intended for the bushcrafter, wildcrafter, or naturalist who wants to produce small batches for a family meal.

IMPORTANT:

|

The Original “Superfood”

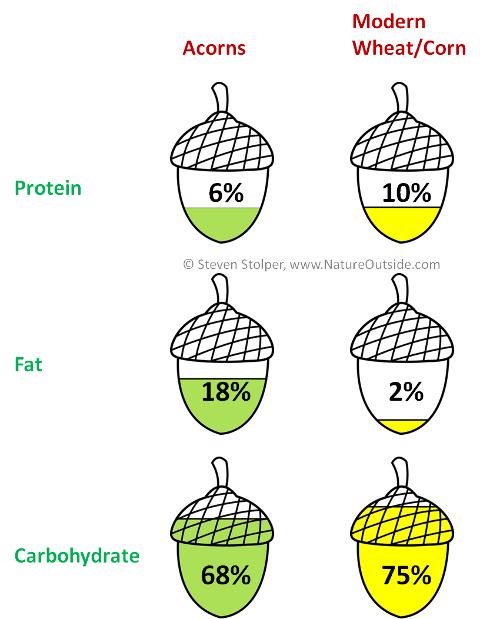

Acorns are very nutritious. But what makes them unique is that they are high in fat as well as protein. This combination is unusual for a plant-based food. It allows you to obtain fat and protein without expending many calories hunting animals.

Native Californians appreciated this characteristic. Almost every Native American tribe west of the Sierra Nevada harvested acorns for food. Anthropologist Alfred Kroeber estimated that, at the beginning of the last century, 3/4th of all Native Californians relied on acorns for daily meals1.

Acorns are calorie dense and a complete protein. Nutrient content varies by species. But I have put together a table that compares generalized acorns to modern varieties of wheat and corn:

Data from “Oaks of California” (see references below).

Acorn line drawing courtesy of sweetclipart.com.

Acorns Step by Step

Bedrock mortars for grinding acorn

Using acorns as a wild food consists of these steps:

- Selecting and harvesting

- Drying and Storage (optional)

- Shelling

- Grinding

- Leaching

- Cooking

Don’t be deceived by the number of steps! Processing acorns is really very simple. When you try it for yourself, you will understand that it is harder to write the steps than it is to actually process the acorns.

I have broken the entire process into bite-size pieces (pun intended). This article will cover steps 1 & 2 with two more articles to follow.

Selecting and Harvesting

We only want to collect and process “good” acorns. These are ripe acorns that do not suffer from weevil infestation or fungal infection. Shelling acorns only to find weevils or worse, weevil poop, is no fun! Fungal infestations decay the interior and can ruin the party as well.

There are visible signs that warn that an acorn is bad. You can train yourself, with practice, so that you almost never gather bad acorns. But expect a small percentage of your acorns to have problems.

For guidance in selecting good acorns, read Nature’s Garden: A Guide to Identifying, Harvesting, and Preparing Edible Wild Plants, by Samuel Thayer. Thayer describes the most helpful and systematic approach I have found for gathering good acorns.

My yield is currently about 90%. Eventually your eyes prevent you from selecting acorns infested with weevils or fungus. As you gain more experience you will become a super-efficient acorn forager.

Again, I refer you to Thayer for a wonderful tutorial on how to select good acorns. But here are some of my tips for avoiding “bad” acorns:

- If it is on the tree, let it be!

- If the acorn is green, leave the scene!

- If the cup is on, acorn begone!

- An exit hole is not our goal!

- You must watch for the dark splotch

I gather mostly tanoak acorns (lithocarpus densiflora), which are large. About 20 of them yield a cup of acorn meal.

Many Native Californians used a conical burden basket to collect acorns. I employ a small deerskin bag that I made for this purpose. When the bag is full, I know I have gathered enough. I leave the rest to the forest.

Forget the Float Test

From time to time, people ask me about using the “float test” to detect bad acorns. Samuel Thayer, in his book Nature’s Garden, says that “good” acorns are heavier than water. As they are eaten by weevils, they become lighter.

I have tried the test several times, and it works. But there are a number of limitations so I do not use it anymore.

- It only catches acorns that have been consumed by weevils to the extent that they float.

- It only works on fresh acorns. Once I started drying them, I abandoned the float test.

- Any acorns that have dried a bit might float.

Thayer still advocates visual inspection over the float test, and I agree.

If you are storing acorns for any length of time, you want to minimize their exposure to moisture. So doing the float test on newly collected acorns is a pain. You would need to remove the excess water before the drying/storage phase.

Drying & Storage

When I started gathering acorns, I was so eager that I collected and processed them the same day. However, drying acorns gives you a ready supply whenever you feel like processing them. In my opinion, the dried acorns are also easier to handle.

When you gather acorns, conduct good visual inspections at harvest time and after you get home. I place my acorns into a ceramic baking dish and leave them in a cool dry place, away from the sun. The high walls of the baking dish prevent any weevils that hatch from climbing out. Good air circulation is important, so I often leave the dish on a shaded counter-top. Inspect your acorns periodically for evidence of weevils. Dispose of any weevils you find along with the bad acorns (You can recognize them by their exit holes).

The acorns will usually undergo a uniform color change as they dry. This is normal.

Drying times vary. I usually forget about them for a week or two. When I am certain they are dry, I store them in the refrigerator. Refrigeration is not necessary, but it is what I do.

References

- Oaks of California, Bruce M. Pavlik, Pamela C. Muick, Sharon G. Johnson, and Marjorie Popper

- Nature’s Garden: A Guide to Identifying, Harvesting, and Preparing Edible Wild Plants, Samuel Thayer

Here are the other articles in this series:

Part 2: Equipment, Shelling, Tannins, and Grinding

How to Make Orange Acorn Bread

If you liked this article you might also enjoy others in the edibles section or the skills section.

Great post! I have read Nature’s Garden book by Samuel Thayer. It’s very well thought out book on foraging, excellent book to cross reference with edible wild plants.

Thanks, David! I’m glad you like the article. Both of Thayer’s books are excellent references for people who forage for wild edible plants.