The pond is beautiful. And I pause to gaze into its placid waters.

A spring emanates beneath its surface from deep within the Santa Cruz Mountains. During the 1950’s ranchers built an earthen dam around it to water their hogs. Now a nature preserve, the pond is ringed by cattail beds and teems with vibrant bird life.

Through unmarked time the stream spilled downhill into the forest. I glance over my shoulder into the ravine that the river carved when it flowed. Ancient Tanoak and Douglass fir stand sentinel awaiting the stream’s return. Their dark shadows look inviting as I loiter in the dazzling sun.

I know that “downstream” from my position the Ohlone people drew its water to leach tannins from acorns they used for food. Their ancient bedrock mortars haunt the now dry creek bed.

Despite the cool temperature I am sweating from my hike. I find a cozy spot along the bank and settle down to lunch. Satisfied, I munch my sandwich looking up at the grassy hills caressing the crystal sky.

A beautiful day at the pond

Narrow leaf cattail rings the pond. An American coot swims in the distance.

The Wily Coot

In the distance I see an American coot (Fulica americana) foraging among the reeds. I recognize it by its black feathers, distinctive silhouette, and staccato coot, coot, coot chatter. It’s unusual to see one here. They prefer a larger pond several miles away.

As I rummage through my pack, my eyes are drawn back to the bird. It’s behaving strangely. Coots usually swim away from people on the bank. They are shy animals who retire to the center of a pond the moment you appear near the water’s edge.

But this one is approaching. In fact, it crossed the entire width of the pond to reach me. Bad news! This bird must have been fed by people. It’s discarded natural caution in the hopes of a handout.

I take advantage of its arrival to shoot a few pictures. It waits expectantly for food, but quickly grows bored with my noncompliance. I watch as it disappears beneath the surface, foraging for plants growing on the bottom.

American coot (Fulica americana). Look at those amazing feet!

Coots are really charcoal colored. This one’s feathers look bright because of the sunlight they reflect.

The bill is bright white. Coots have a frontal shield, which is a fleshy rearward extension of the upper bill.

Normally, coots flee from humans

Coot feeding on plants pulled from the bottom during a dive

What is a Coot?

I like coots. As an urban kid from the East Coast, I never saw them before I moved to northern California. They are highly vocal and strangely charismatic.

They look like ducks, but they’re not! Coots are members of the Rallidae family, more closely related to the cranes and rails that prowl the shoreline. Coots are about the size of a chicken. Their charcoal feathers and bright white beak are distinctive even when viewed from afar.

They eat aquatic plants including algae, duckweed, eelgrass, sedges, waterlilies, and cattail. Like ducks they pluck at plants and dabble. But they also dive to the bottom, disappearing in an instant and resurfacing with tendrils of green dangling from their mouths.

Although coots swim like ducks, they don’t have webbed feet. Each of the coot’s toes has large flaps of skin that act like flippers. They fold back whenever the coot raises its leg so they don’t trip the bird while it’s walking.

What amazing feet! The flaps act like flippers and fold up when its foot is in the air. Photo by Maggie Smith (CC2.0)

I look for coots in freshwater wetlands with heavy stands vegetation lining the shore. I often see them swimming in and out of cattail or tule reeds that line the shallows.

Here is a link where you can listen to coot vocalizations.

The Coot’s Secret

All animals live secret lives. And looking at the diminutive coot you wouldn’t suspect anything strange or exotic. But you’d be wrong!

During my naturalist training, Professor Bruce Lyon from the University of California, Santa Cruz lectured to our class. He is trying to understand the ecological and evolutionary basis of reproductive strategies. And he studies coots. Why? Because the American Coot has a doozy of a reproductive strategy.

Coots are conspecific brood parasites. They’re what?!! Coots will lay their eggs in the nests of other coots. More than 200 species of birds are known to do this, but coots seem to have perfected the art.

An average hen will lay 8 eggs1. But in his studies Professor Lyon found as many as 17 parasitic eggs in a nest. Imagine finding a nest with 25 eggs in it! That’s a lot of sneaking around and laying in other hen’s nests. What is going on?

Why would a female coot choose to lay her eggs in the nest of another? Isn’t she better off raising her own chicks?

There are several reasons why the birds might choose to do this3:

Best-of-a bad-job (BOBJ)

Females lay parasitically when their environment or physical condition limits their ability to breed otherwise. Environmental conditions are unfavorable for them to raise their own brood. So they choose to lay them in another’s nest with better prospects.

Nest loss

If their nest is destroyed, females lay parasitically because it is their only hope of reproducing that season.

Lifelong specialist parasites

Females depend entirely on other females to raise their offspring so they will not experience the burdens of parenthood. This allows them to enjoy a longer reproductive life because they are free from the stresses of raising their young.

Fecundity enhancement

Females lay parasitically in addition to having a nest of their own. This allows them to bypass some of the constraints of parental care. If they can only care for so many hatchlings, having others raise their children allows them to have more than just nesting alone.

Which of these is driving the coot’s unusual behavior?

It Makes no Sense, but then It Does

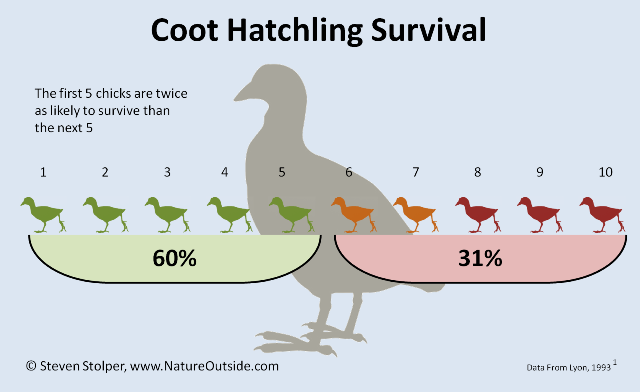

When Professor Lyon looked at hatchling survival rates, things began to fall into place. He discovered that the first 5 chicks to hatch had double the chance to survive than the next 5 chicks.

This makes sense. Hens lay one egg each day. So if a female coot lays 13 eggs, the oldest egg has a 13-day advantage over the youngest. This is a tremendous advantage in size and development.

When he looked at the actual causes of hatchling death, things became even more interesting. His findings show that chick mortality occurs mainly due to starvation rather than predation. Most chicks died in the first 10 days after hatching, when they are most dependent on adults for food. Food is the limiting factor! And which chicks survive depends on the parent’s ability to feed them.

Most female birds lay more eggs than the parents can rear. During plentiful times, this leads to increased success because more chicks grow to adults. But under normal conditions, they lose young to starvation or predation.

What does this have to do with laying eggs in other coots’ nests? If you are a hen laying egg number 11 in your own nest, that chick has a poor chance of survival. But if you can sneak over to another nest where it can be egg number 5, your chick stands a much better chance. You have a powerful motive for laying your eggs in another’s nest even when you have a nest of your own. But while you’re gone, other hens are doing the same to you!

This seems to account for female coots laying eggs in another’s nest even when they have one of their own. And as a result, there is a lot of sneaking around and covert egg laying in the life of a female coot.

Other hidden lives

The coot is a terrific example of an unlikely animal that leads a fascinating hidden life. Can you think of others? Let me know in the comments below.

More Birds on NatureOutside

Birds Think You are a Scary Dinosaur!

Owl Class – The Harry Potter School of Bushcraft

What we can learn from a Harrier’s Butt

Where do Birds go When it Rains?

References

1. Lyon, B.E. 1993. Tactics of parasitic American coots: host choice and the pattern of egg dispersion among host nests. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 33: 87-100.

3. Lyon, BE & Eadie J.McA. 2008. Conspecific brood parasitism in birds: a life history perspective. Annual Reviews of Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 39: 343-363.

For fun facts and useful tips, join the free Bushcraft Newsletter.

Fascinating stuff, Steve! No biology facts to add – but it brings to mind one of my kids old bedtime stories: “Horton Hatches an Egg,” and lazy bird Mayzie, who gallivants off to Florida (I think) while faithful Horton sits on her egg… a nice moral about dedication but some very unscientific biology in that story.

Susan, I wonder if Mayzie was a coot! 🙂

I was watching a group of coots today close to the shoreline in quite a big gathering very close together, diving and almost playing like behavior then more wold come to the close knit group and start doing the same thing as others would leave….never saw this behavior before do you know what is happening?

Kym, I don’t know for certain what is happening. Near me, they’re forming large flocks and it is the start of breeding season. According to the Audubon Society, courtship displays include, “… swimming with head and neck lowered, wings arched, tail raised to show off white patches.”

I also see group feeding behavior when they find an underwater food source. In this case, I see many birds appear to be doing the same thing.

Keep watching and see if you can figure out this riddle!

I live in Virginia Beach, VA. We walk around a lake at Mt. Trashmore Park. There is a Coot living on the shore with ducks. There have been Coots in the park before, but usually in larger groups. Right now, he is the only Coot there. He eats with the ducks and grazes with the ducks, but I worry he has no other Coots to be with. He seems healthy and happy.

Jan, I’m sure the Coot you see is fine. It is currently breeding season, and the Coot’s friends are probably up north breeding. For some reason, this Coot decided to stay in Virginia Beach. And who can blame him (or her)! 😀 It is possible that this Coot is immature and decided not to migrate. Coots reside all year long in areas of the western US and Florida. Perhaps this Coot is starting to reside full-time in Virginia Beach.