I scan the marshland as the early morning breeze sways what remains of my hairline.

From my position I can see Great Egrets (Ardea alba) and Black-necked Stilts (Himantopus mexicanus) wading at the waterline. American White pelican (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos) enjoy the morning sun on an island protected by deeper water. Beyond the tranquil marsh, the San Francisco 49’ers football stadium looms in the distance. The 68,000-seat arena is an incongruous backdrop for such a peaceful scene.

Suddenly, the silence is shattered by a whirlwind of motion and youthful energy.

Tiger Scouts! I never heard of them before they arrived for the hike. Tiger Scouts is a program of the Boy Scouts of America for boys from first through fifth grade (7 to 11½ years old).

I’m leading a 5-mile hike for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. We’ll explore a salt marsh with its specially adapted plants and wildlife. These are mostly first-grade boys. I wonder if they will have the endurance for a 5-mile trek.

New Chicago Marsh

We’re in the Don Edwards San Francisco Bay Wildlife Refuge. This is the southern-most tip of the bay, about 40 miles from the city of San Francisco.

We’re here to explore a rare and important habitat that is disappearing from the United States.

Salt marshes like this one are found on the low-lying lands between the open waters of San Francisco Bay and the dry ground of the uplands. Flooded by daily high tides, they are salty, watery worlds of their own. Humans can live almost anywhere, but many of the salt marsh’s plants and animals can live nowhere else. Their unique adaptations tie them to this habitat.

New Chicago Marsh

The marsh lies between the upland and the deeper water of the bay.

Salt marshes are extremely important for both people and wildlife…

Food

These marshes provide food for millions of birds. When the tide goes out, Western Sandpipers (Calidris mauri) find food on the exposed mudflats. Sandpipers are migrating birds. The food they find in salt marshes gives them the fuel to fly from San Francisco to Alaska.

The California Clapper Rail (Rallus longirostris obsoletus) lives its entire life in the salt marshes. It hunts worms, mice, and insects.

Shelter

Steelhead trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) begin and end their lives in freshwater streams. But the majority of their lives are spent in the ocean. Salt marshes provide a safe passage between these two worlds.

Salt marshes also act as nurseries for crabs, shrimp and fish. Young larvae and fry live in the marsh’s protected waters until they are big enough to survive the Bay’s open waters.

Protection for People

Salt marshes protect people in two important ways. During floods, marshlands help us by slowing and absorbing flood waters. They also act as water filters, cleaning water for both wildlife and people.

Helping to Restore Salt Marshes

Adventure Monkey helps guide Tiger Scouts (seven years old) through a National Wildlife Refuge.

As you might guess, salt marshes are a disappearing habitat. More than 85% of the Bay’s wetlands have been lost to human development.

When salt marshes disappear, the plants and animals adapted to it lose their homes.

That was once Chicago Marsh’s destiny. A developer in 1890 sold 3,500 of 4,000 housing lots on the site. He called the development, “New Chicago.” But the project ran into financial trouble and marsh was never developed.

Now it is one of the last pieces of historic salt marsh in the area. It’s surrounded by commercial salt ponds, neighborhoods and landfills.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is restoring Chicago Marsh for both wildlife and human recreation. It’s still managed by people, but the hope is to return it to a natural tidal marsh.

The Strange Pair of Tracks

At the start of the hike, our group travels across a raised boardwalk. The boardwalk keeps hikers from being bogged down in the mud. It also protects the pristine surface of the marsh from human disturbance.

I relish this part of the hike. From our raised vantage point it’s easy to spot tracks left behind by the marsh’s residents.

This hike is true to form. We quickly find some small canine tracks in the mud. The tracks run underneath the boardwalk and the trail is easy for the children to follow. Domestic dogs aren’t allowed in the preserve. That doesn’t mean people never bring them in. But the nature of the muddy marsh tends to keep the domestic dogs at bay (pun intended).

Gray Fox tracks in the mud

These tracks are made by a gray fox. They’re beautifully preserved in the fresh mud. Normally, I make a plaster cast and give it away to a member of the group. The casts take an hour to set so I retrieve them at the end of the hike. But the young children are making slow progress and I feel we don’t have time to stop and make a cast.

The yellow star indicates the trailhead. The red star shows where we found the fox tracks.

Map by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Annotated by NatureOutside.

I vow to return after the hike to make one for myself.

Take nature home with you – Legally!

Many wild places in the United States exist today because people chose to protect them. Laws and regulations forbid removing plants, animals, rocks and organic material. This makes sense because humans are so numerous. Just a small fraction of our population can denude a forest by taking down trees or collecting plant specimens.

But I enjoy having nature in my home. I made a small basket from vegetable-tanned leather and tooled it with symbols of bushcraft and nature. It holds small mementoes from previous trips in the outdoors. These include feathers, California Buckeye nuts, and honeycomb. All were collected where permitted by law.

But my prized possessions are animal tracks preserved as plaster casts. It’s almost like bringing the animal home with you. Each track reminds me of the time I spent analyzing or following the animal. My collection includes Mountain lion, Gray wolf, and Gray fox. The beauty of making plaster casts is that it is perfectly legal in most areas. Just be careful not to leave a mess behind.

Small natural and hand-crafted items keep me connected to nature even when I’m stuck indoors. But collect only where the law allows.

A while back, I posted detailed instructions for how to make plaster casts of animal tracks. In that article, I make casts of captive Gray Wolf tracks. I use the same technique here, with one modification.

To make a thicker base for the cast, I’ve started using plastic rings cut from Solo cups. These are the ubiquitous red cups found at parties across the nation. I cut several cross-sections at various heights and I get frames that fit different size tracks.

I carry the plaster in a zip-lock bag in my pack. I also carry a paper bag to store the finished cast. Inside the bag, I keep the plastic rings and a plastic spoon for mixing the plaster. Water from my water bottle does the rest.

Mixing the plaster is easy and takes only a minute.

I place the plastic ring around the track and pour in the plaster. It takes about an hour to harden depending on environmental conditions.

I previously arranged permission to step off the boardwalk to cast the tracks. It takes an hour for the plaster to set.

Adventure Monkey and me waiting for the plaster to set. I usually leave the cast and return later to collect it.

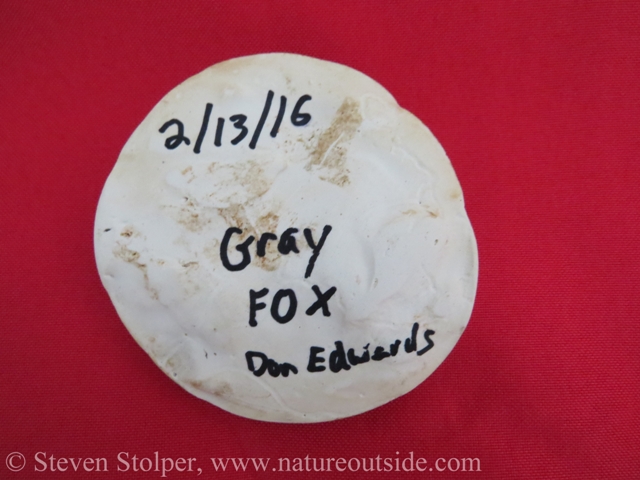

Once the plaster dries, I carefully scoop it out of the mud. I let it continue drying for a day after I return home. Only then do I brush the dried mud from it. I note the type of animal, date, and location on the back of the cast. Then I apply a clear polyurethane coating to keep the cast from drying out and increase its durability.

The finished cast of the Gray fox track. There is some dirt I can’t remove without sanding. I choose to leave it to preserve the detail in the track.

I write information about the animal and where I found the track using a felt-tip marker. I let the writing dry before I apply the polyurethane.

You may notice the dirt I couldn’t remove from the cast. If you want a “clean” track, you can sand it to get a pure white finish. But I never do. Sanding removes a lot of the detail that makes the track interesting.

It’s Fun and Easy

Making casts of animal tracks is fun and surprisingly simple. And it is easy enough to master that anyone can learn to do it. Try it yourself and let me know how it goes by leaving a comment below.

References

I used material from interpretive signs found at Don Edwards San Francisco Bay Wildlife Refuge

Related Articles on NatureOutside

Adventure Monkey – Getting Young Children Outside!

Wolves Teach a Master Class (Part 3)

Mountain Lion Tracks – Learn to Read Them

For fun facts and useful tips, join the free Bushcraft Newsletter.

Leave a Comment